Brokeback Mountain

Program Notes

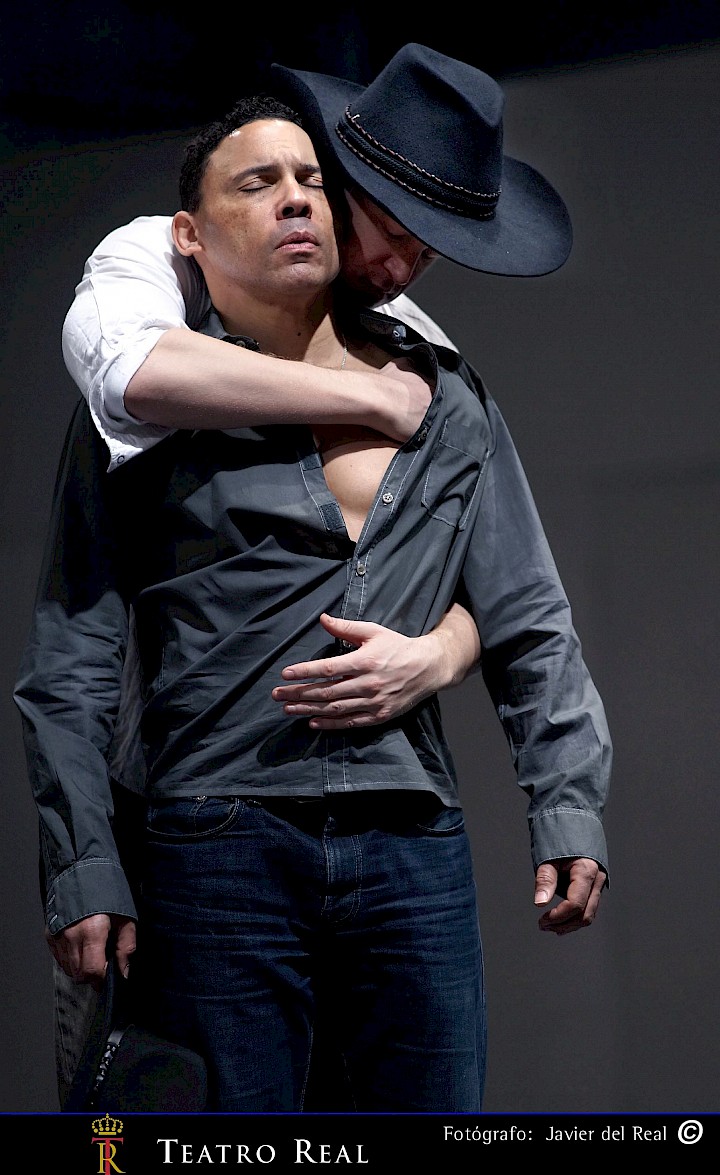

Brokeback Mountain dominates this and other scenes.

—descriptor from Scene 1 of the score of Brokeback Mountain

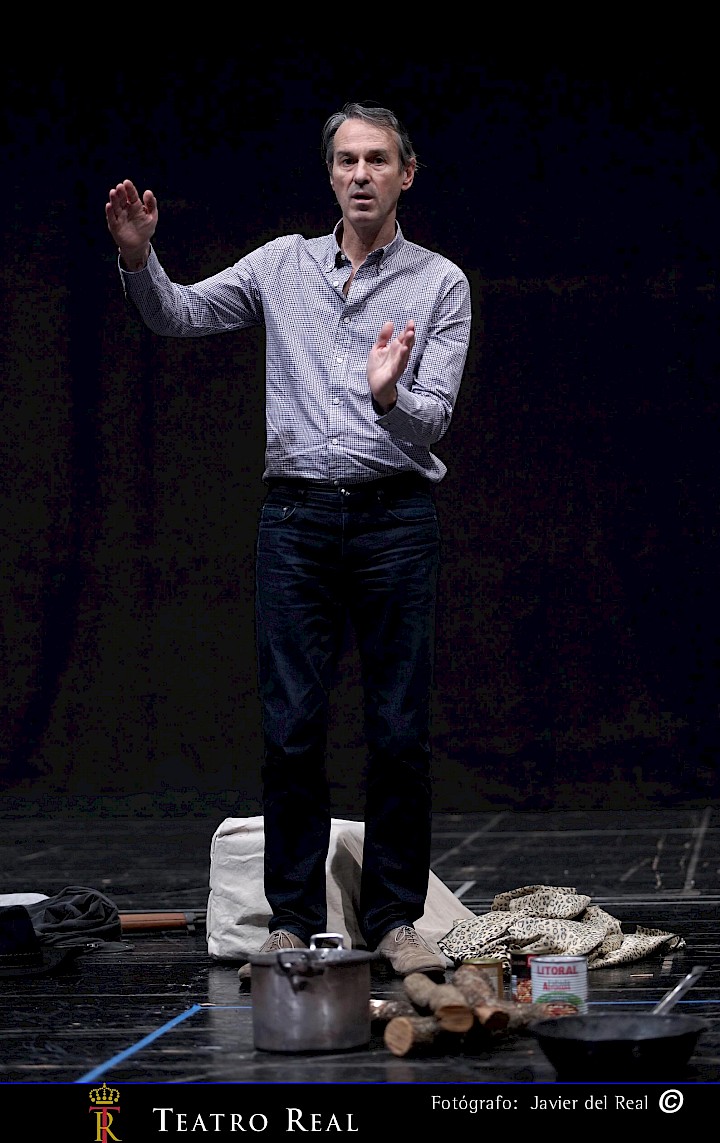

Brokeback Mountain is the American composer Charles Wuorinen’s third opera, based on a short story by the Pulitzer Prize-winning American author Annie Proulx. Originally published in The New Yorker magazine in 1997, the story was made into a film by director Ang Lee and reached U.S. theaters in late 2005. The film version called the story to Wuorinen’s attention and first suggested possibilities for an opera. Although ultimately co-commissioned by Madrid’s Teatro Real, discussions for the opera’s first production had originally begun with New York City Opera, which a few years before had staged Wuorinen’s acclaimed Haroun and the Sea of Stories, based on Salman Rushdie’s children’s book. Unlike Brokeback Mountain, Haroun and an earlier opera, The W. of Babylon, are comedies.

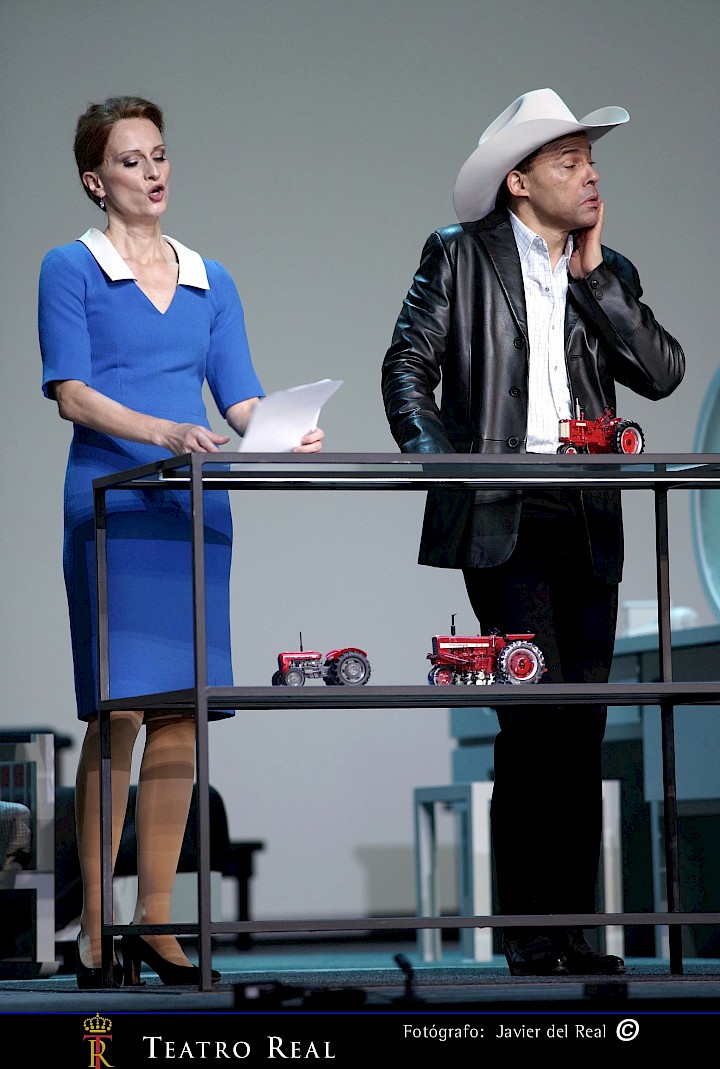

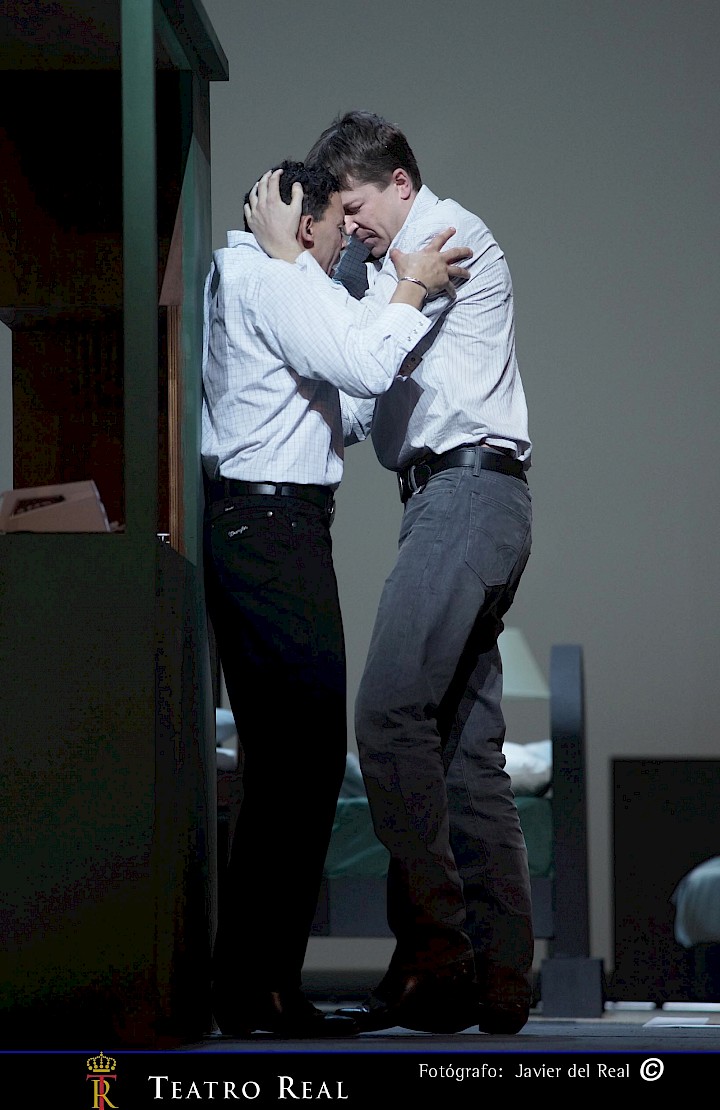

The libretto for Brokeback Mountain was written by Annie Proulx herself, following a period of persuasion to take on a medium she had never attempted. The wisdom of such a collaboration was borne out by the results: in language distilled to that which can be sung onstage, the story’s details and themes remain intact, but the method of its telling required significant changes. Descriptions and situations developed in the original prose have been clarified via scenes only implied, or altogether missing, from the story, for example the scene in which Alma buys her wedding dress. The author also allows, indeed expects, Wuorinen’s music to provide the geographic and psychological landscapes in which the story takes place. The music also amplifies and colors the emotional content of the characters’ sung words. Opera’s great and compelling strength is its ability to project this mysterious, multilayered world.

Annie Proulx’s work creates both character and place: her Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award-winning 1993 novel The Shipping News places its protagonist Quoyle in the strange and initially unforgiving landscape of Newfoundland, Canada, and detailed the transformation of the character’s and land’s relationship to one another. The story “Brokeback Mountain” appears in her collection Close Range: Wyoming Stories, in which the U.S. Western state of Wyoming—a land of mountains, cattle and sheep ranches, and the ever changing confrontation of tradition and progress. The men and women populating these stories also find themselves struggling with identity and change. Proulx, armed with humor and compassion as well as unflinching clarity, asks that we encounter both the environment and its people with sympathy, regardless of our own prejudices and expectations. The resulting worlds, conjured jointly by author and reader, are rich and dynamic.

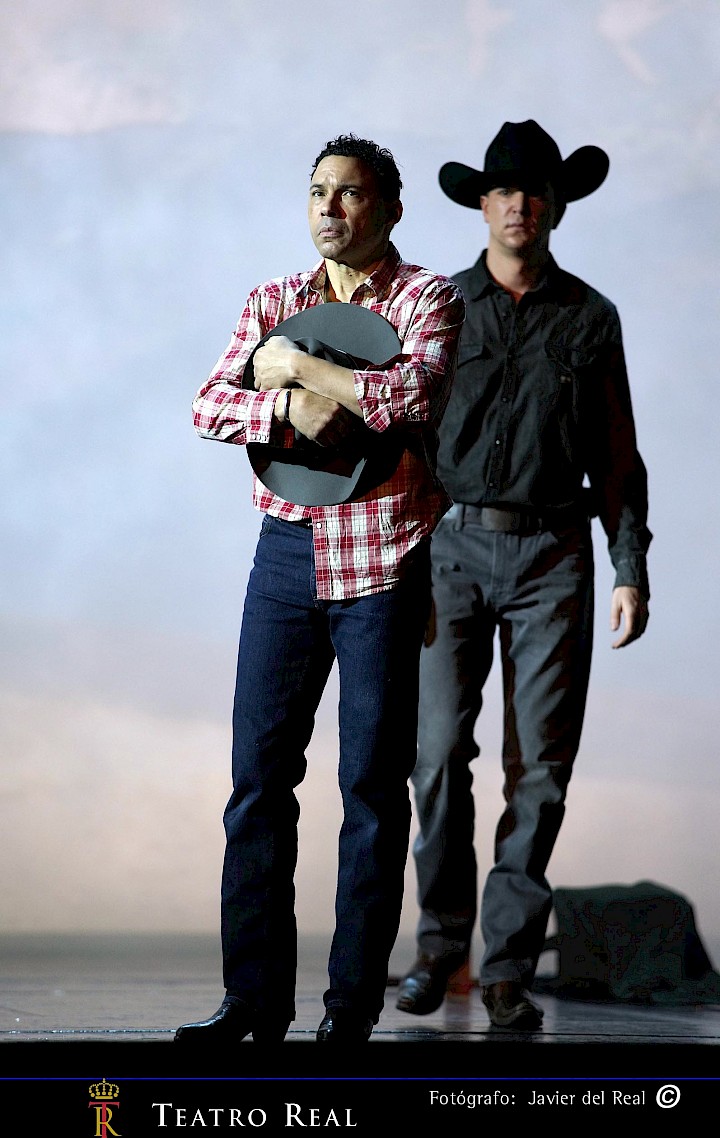

Just as Proulx’s prose moves fluidly between human characters and the landscape, Charles Wuorinen’s music moves through a variety of modes. The bass-heavy music we hear at the start of the opera definitively invokes the mountain, its power and vibrant energy, its purpose akin to that of Wagner’s river music at the start of Das Rheingold, the sea in Peter Grimes. Like the mountain, this music is potentially present at all times, sometimes indicated with just a single short dark note at the bottom of the orchestral spectrum. The orchestra shifts between this and more local concerns, driving the energy (violent, raucous, tender) of individual scenes, with orchestral Interludes adding detail and scope, as well as resetting our sense of the mountain, for the next vocal scene.

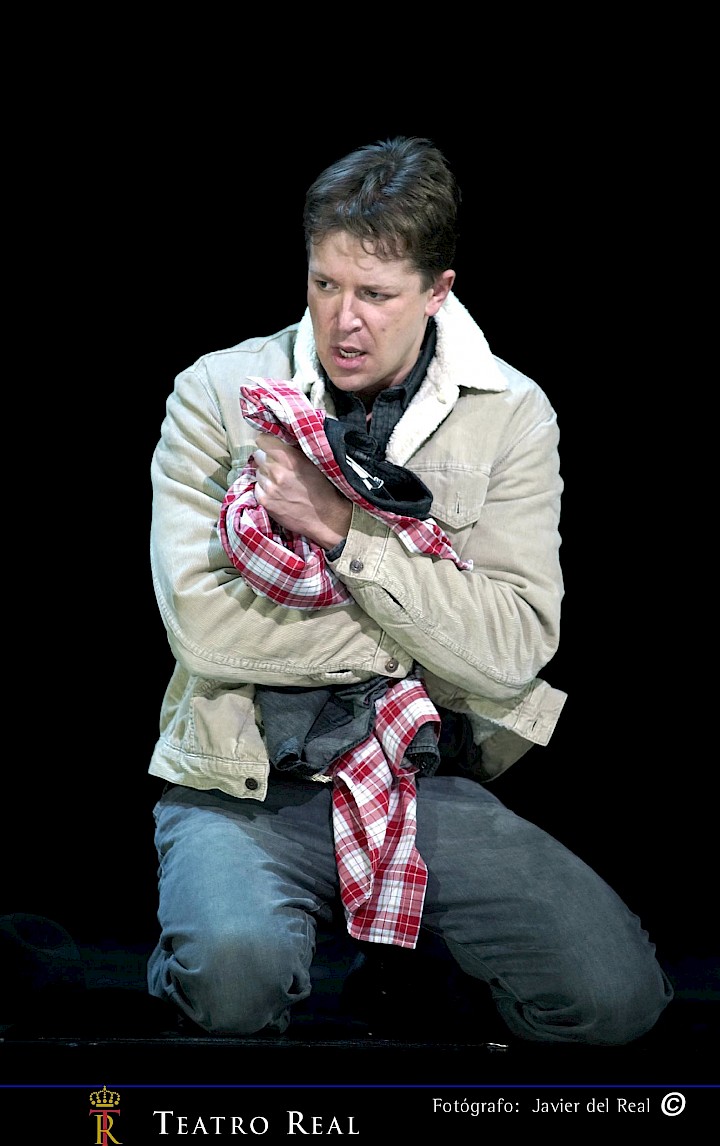

The vocal music also shows transformation: Aguirre’s solo scene at the beginning moves from declamatory impatience to an aria of respect for the mountain. In Jack and Ennis’s first scene together in the bar, their characters are defined, talkative Jack’s line has range and flexibility, while Ennis’s utterances are virtually speech. As he grows more comfortable with his new friend, Ennis begins to sing, an evolution that continues throughout the opera. (Wuorinen relates the contrast between these two vocal styles to the characters of the eloquent Aron and the reticent Moses in Schoenberg’s opera.) Wuorinen and Proulx also employ a few operatic conventions, acknowledging the history of the genre: in addition to the orchestral prelude and interludes, the presence of aria and vocal duets and ensembles, there is even a ghost (Jack’s wife Lureen’s father, Hog-boy). There is one scene for chorus, near the end of the second act, which Wuorinen equates to the Greek tradition of the Furies. Such conventions, as well as the emotional depth of the piece as a whole, embed the wholly divergent worlds of rural Wyoming and European operatic tradition deeply within one another.

***

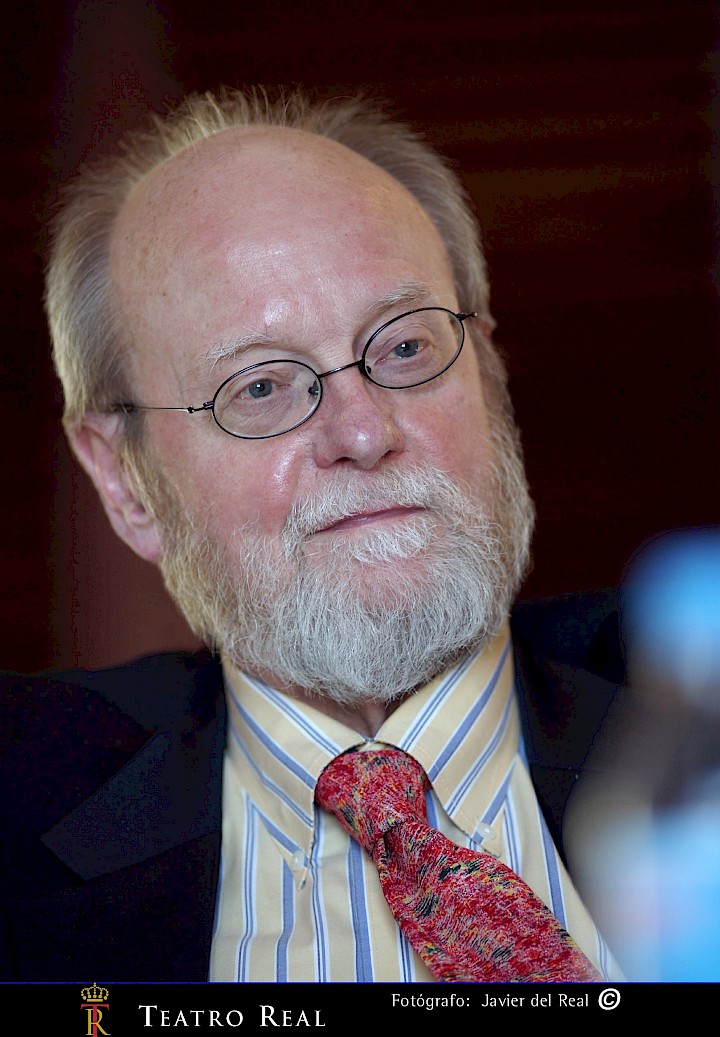

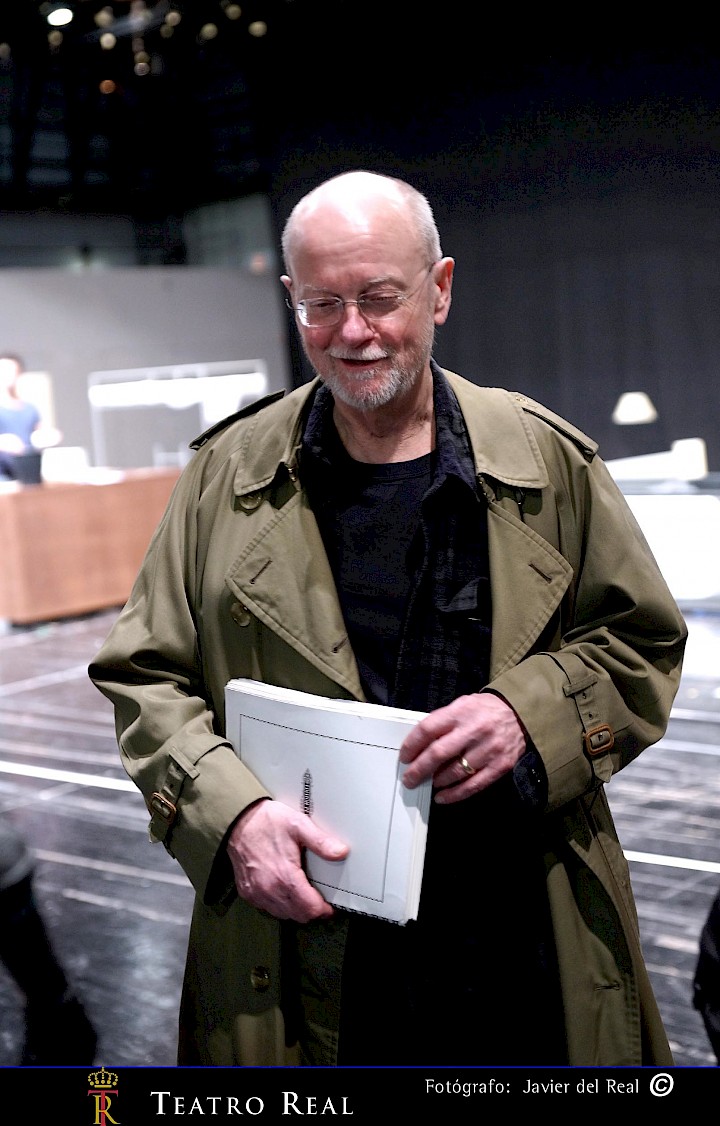

Annie Proulx is the latest of a number of major artists with whom Charles Wuorinen has worked, a list of whom would provide probably unneeded evidence of the celebrated composer’s status. Since his earliest days as a professional musician, relationships have been helped invigorate Wuorinen’s development. After beginning to compose at a very young age, he made great progress also as a pianist, making his public debut at fifteen. After winning recognition for his compositions, including the New York Philharmonic’s Young Composers Award, he attended Columbia University in New York City to earn both his undergraduate and graduate degrees. While at Columbia, he embarked on what has been a five-decade journey of advocacy for serious classical music by founding the Group for Contemporary Music with composer/flutist Harvey Sollberger and cellist Joel Krosnick. Wuorinen served as pianist and conductor for the Group as well as guiding its repertoire, which included not only his own and its members’ work but much important modern music that had little exposure elsewhere in the United States, including that of Webern, Berg, Wolpe, Chou Wen-Chung, Berio, Boulez, and Stockhausen, as well as the Americans Sessions, Luening, Carter, Babbitt, Shapey, and many others. The Group has served as a model for generations of younger ensembles through its variety of repertoire and the excellence and virtuosity of its musicians. Wuorinen’s work as an advocate continued beyond the GCM, and has included curating repertoire with the American Composers Orchestra, the Tanglewood Music Center, the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, and elsewhere. He also taught at Columbia University, Princeton, Yale, the New England Conservatory, and the Tanglewood Music Center, among many others.

Wuorinen saw to it that music of the Medieval and Renaissance periods, from Perotin to Thomas Morley, also appeared on the GCM’s programs, feeling that that music’s complexity illuminated connections between the modern and the past. Re-composing and arranging works of the past has consistently been a part of Wuorinen’s compositional activity. This speaks to his belief that his work is not a break from, but rather a continuation, of the long tradition of conservation and renewal in Western music. Active throughout most of his professional life as a pianist and conductor, Wuorinen is, in the broadest and most fundamental sense, a musician, inviting comparison to the musicians of eras before the peculiarly late-20th century ascent of the composer-as-specialist. His music suggests that the idea of “contemporary” includes not only the modern but details and ideas from musical history filtered by posterity—20th-century developments by Schoenberg and Stravinsky as well as earlier music.

Of more recent strong influences, Stravinsky suggested primarily style—rhythmic vitality, textural clarity and variety. Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique was a model for method and robust architecture. Wuorinen also followed Milton Babbitt’s lead in extending the serial technique to other aspects of musical structure, especially rhythm and the proportions of longer timespans: phrase, episode, movement. His later research into fractal geometry enriched and expanded this approach to thoroughgoing structural integrity. Another important facet of Wuorinen’s career that parallels composers of the past—Bach, Mozart, Stravinsky—is his willingness to recontextualize his own earlier compositions, for example in his extraction of the material of Flying to Kahani, The Haroun Songbook, and The Haroun Piano Book from Haroun and the Sea of Stories; Contrafactum, his orchestral version of the electronic piece Time’s Encomium; and multiple orchestrations of various other pieces.

Performances by the Group for Contemporary Music of many of Wuorinen’s important early compositions showcased the brilliance and individuality of his musical language. Among Wuorinen’s significant works of the 1960s played by the Group were several chamber concertos for solo instruments and ensemble; Ringing Changes for twelve percussionists, and The Politics of Harmony, his first work for the stage. In 1969 he completed his only extant work for tape alone, Time’s Encomium, commissioned for the Nonesuch Records label. The piece won the Pulitzer Prize, the major U.S. award for music composition, in 1970; it was the first piece of electronic music to win a Pulitzer, and at the time Wuorinen was the youngest-ever winner of a Pulitzer in music. (In addition to the Pulitzer Prize, he has been recognized with a MacArthur Fellowship as well as memberships in the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.)

Partly on the strength of the Pulitzer Prize, in the 1970s Wuorinen began to develop connections with various major orchestras. He wrote his Concerto for Amplified Violin and Orchestra for the Boston Symphony Orchestra and his Second Piano Concerto for the New York Philharmonic. Other commissions came from the American Composers Orchestra, the Milwaukee Symphony, the Cleveland Orchestra, and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

The breadth of Charles Wuorinen’s engagement not only with music but with literature, history, science, and other cultural ideas is remarkable, and recognizes their intertwining. Echoing the works of earlier masters, Wuorinen has pursued a number of challenges both technical and contextual, in order to solve them musically. Bach, for example, worked out the technical issues of counterpoint and questions of national and generational style via such collections as the Goldberg Variations and the Well-Tempered Clavier. Beethoven delved into philosophical as much as into musical matters in marrying sonata and variation form with fugue in the late piano sonatas, the Grosse Fuge, and the Ninth Symphony. Wuorinen’s steps along the way have included the comprehensive exploration of structural duration in Time’s Encomium; re-establishment of pitch centers within an integrated serial (and twelve-tone) context throughout the 1970s, in such works as Speculum Speculi and Grand Bamboula; and demonstrations of correspondences between natural processes (e.g., the formation of clouds or the growth of plants) and intuitive musical ideas via study of fractals in such works as Bamboula Squared; and the re-composition of older music in Machault mon chou, the Mozart-based Delight of the Muses, and many other works. His subsequent music has, naturally, built upon each stage of investigation; indeed, these investigations are closely interrelated. His 1979 book Simple Composition is a relatively straightforward explanation of the essential issues of his craft. (Simple Composition, like Wuorinen’s music, is published by the firm C.F. Peters.)

In 1975 Stravinsky’s widow chose Wuorinen to be the recipient of Stravinsky’s last sketches, from which Wuorinen created his Reliquary for Igor Stravinsky, commissioned by the Buffalo Philharmonic and the Ojai Festival. The same year he wrote his first opera, The W. of Babylon, excerpts of which were performed that year by the Group for Contemporary Music. He also worked extensively with such smaller groups as Tashi and Speculum Musicae, but orchestral music figured larger in his output. In 1985–89 he was composer in residence with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra, for which he wrote a number of significant works including The Golden Dance and the large-scale chorus-and-orchestra work Genesis, the latter a co-commission with the Minnesota Orchestra. Choral and vocal music had become a focus for Wuorinen beginning in the early 1980s, with his hour-long oratorio The Celestial Sphere and his Mass for the Restoration of St. Luke in the Fields. Also of great importance were several collaborations with the New York City Ballet and choreographer Peter Martins, particularly the large-scale Dante Trilogy: The Mission of Virgil, The Great Procession, and The River of Light.

In the past decade has had a particularly fruitful relationship with the conductor James Levine, who prompted commissions for the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and the Boston Symphony Orchestra; with the BSO, Levine led the premieres of Wuorinen’s Eight Symphony and Fourth Piano Concerto. The concerto was composed for another champion of the composer’s music, the pianist Peter Serkin. Song became a greater part of Wuorinen’s output since the 1990s, leading up to the opera Haroun and continuing to the present day. Among the poets Wuorinen has set in recent years are Dylan Thomas, James Fenton, Seamus Heaney, John Ashbery, and James Tate, whose work was the basis for the forty-minute, cantata-like It Happens Like This, commissioned by the Tanglewood Music Center. This work for vocal soloists and large ensemble was premiered in a semi-staged performance at Tanglewood in 2012.

The W. of Babylon, Haroun and the Sea of Stories, and It Happens Like This, for all their range and substance, are fundamentally comedies. Brokeback Mountain, it is fair to say, is Wuorinen’s first stage tragedy. In one sense this is something entirely new: but we can also look back at several large-scale, expressively wide-ranging works as the Eighth Symphony, the Dante Trilogy, and The Celestial Sphere for precedent. That being said, the intimacy of our encounters with the characters in Brokeback Mountain lends a level of specific, personal nuance that adds another dimension to Wuorinen’s work. Brokeback Mountain is a major statement in Wuorinen’s career—a career already with many major statements. Drawing on his many decades of experience and marshalling all of his artistic acumen, this sympathetic and fruitful collaboration with the wonderful American author Annie Proulx has resulted in a gripping and beautiful dramatic work that promises to rank among the greatest English-language operas.

—Robert Kirzinger

Robert Kirzinger is a composer and writer based in Boston. He is on the staff of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and has written frequently about Charles Wuorinen’s music.